The Mackay name has been synonymous with demolition for 75 years; current team members reflect on 40 years of business as Grant Mackay Demolition. By Taylor Larsen

The Utah Theatre was built in 1919 and was finally demolished in April 2022 by Grant Mackay Demolition. The company has performed demolition work in multiple sectors, including industrial work like their work on Rio Tinto’s Utah assets.

Arthur Joshua “Josh” Mackay, President of Grant Mackay Demolition, started working in the family business at 13 years old. The third-generation demolition man’s work was less dangerous than swinging the ball and chain at buildings but no less demanding.

“I started at the very bottom fixing diesel tires,” Josh recounted. “I’d get to work on Monday morning and there would be a line of 10 trucks waiting for me to fix their tires. It was hard for a 13-year-old, and my grandpa would come out and help me.”

Today, Josh is the President of the West Bountiful-based company whose roots began over 75 years ago with his grandfather, Arthur Josh Mackay, and his company AJ Mackay and Sons. Josh, nephews Nephi Mackay (son of Grant Mackay) and Dylan Edwards, and business partner Harry Seffker, CFO, are owners of Grant Mackay Demolition Company, a premier demolition company serving Utah and beyond.

Family Legacy

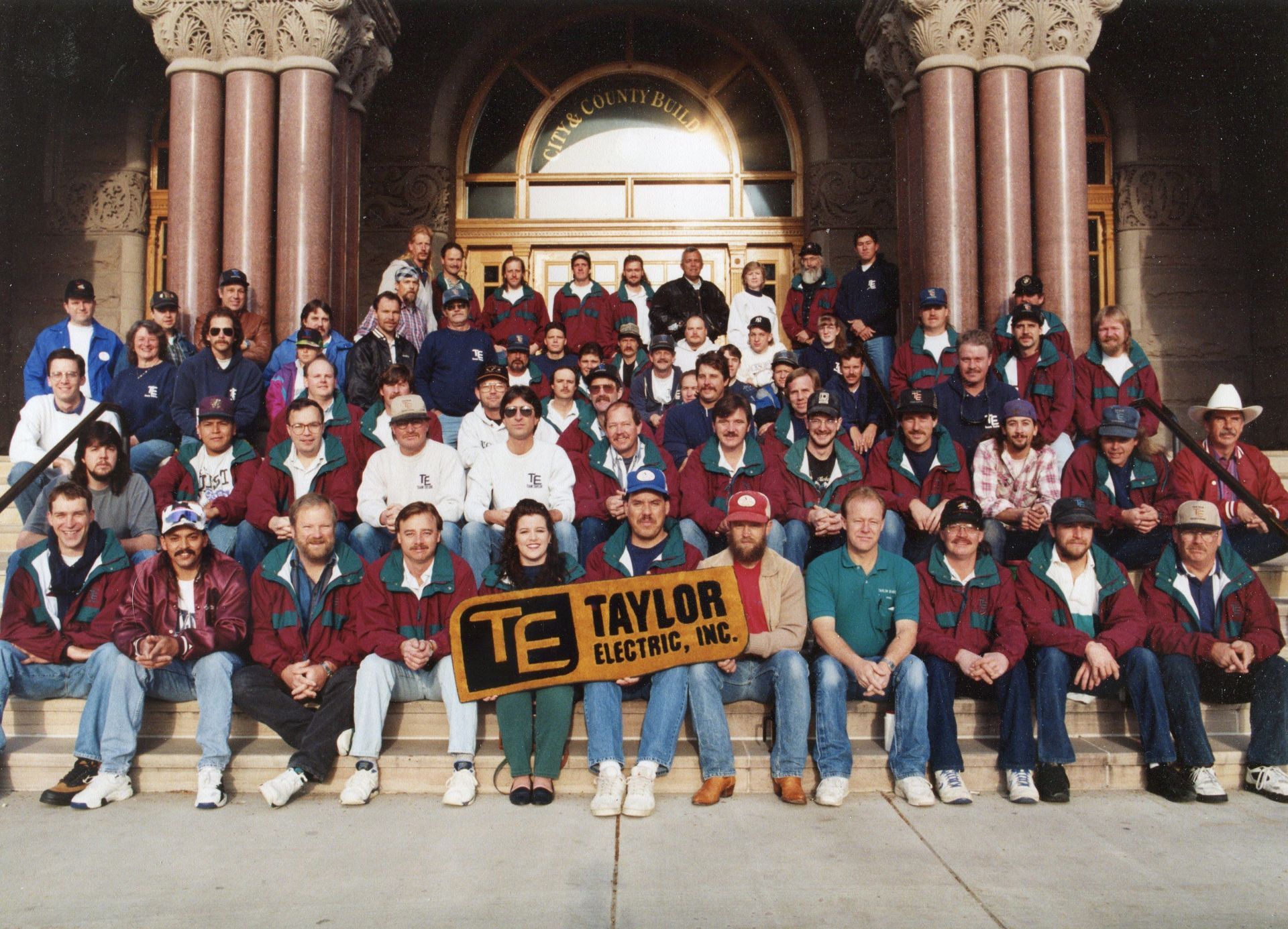

While roles, titles, and even the company name have changed in the past 75 years, many things remain the same, namely the company’s penchant for iconic projects. The beginning of its legacy was refurbishing and demolishing parts of downtown Salt Lake’s City and County Building in 1985. They worked, as Josh described it, to “gut” the building to the stone, preparing the historic structure for seismic upgrades.

Grant Mackay Demolition, the company’s name for the last 40 years, removed half of the City and County Building foundation “like a jigsaw puzzle” to replace it with rubber isolators for Utah’s first-ever base isolation project. “We had guys on their hands and knees doing [demolition] the old-fashioned way,” said Josh. As workers chiseled and shoveled out debris, they uncovered a relic of Utah’s past: an old handcart from the pioneer age long-buried under the building.

It was the last job that Josh worked on with his dad, Clayton Reynolds Mackay, the second generation of Mackay demolition men, who was fighting a battle against cancer before his passing in October 1987.

“He was my hero,” said Josh.

Family has always been a critical component of this business and company, with Josh speaking to how his father and grandfather instilled in him the value of hard work since those first days installing tires. But work was never just a slog, especially when the team went up to Idaho to clean up after the Teton Dam failure in 1976.

“I remember one day we just finished up work there and had a mud fight,” said Josh with a chuckle.

Nephi Mackay, Vice President, spoke of a similar experience growing up in the family business. Grant Mackay, Nephi’s father and Josh’s brother, had a very similar outlook on life to grandpa: work was everything.

Summers in high school had Nephi on job sites holding the fire hose to mitigate dust or sorting through scrap materials.

“There were lots of times with Dad and Josh where we were tearing things down late into the night,” he said. Those times spent learning from uncle Josh how to safely use high-reach excavators or tearing down structures with dad were some of the many memories that make this work so special to him.

Grant Mackay Demolition has been all over Salt Lake—from that City and County Building project to another base isolation project on the Utah State Capitol nearly two decades later in 2004. That project was the starting point for both Nephi and Seffker to begin officially working with the company full-time.

A New Era of Sustainability

Grant Mackay Demolition work has been instrumental in tearing down structures to make way for bigger and better ones. They twice demolished the area that today constitutes City Creek Center, salvaging the iconic ZCMI sign both times before its eventual relocation on Main Street.

Salvaging and preserving is an instrumental part of their profession, the team said, but salvaging isn’t just rescuing artisanal items. More effort has gone to organizing and maximizing the piles of rebar, trees, concrete, and more to help job sites operate at peak efficiency and keep valuable materials circulating.

“Everyone thinks at first glance that it’s so easy,” said Seffker of the intricate work of demolition. “But it’s art.”

One story circulates mid-interview of Josh removing a layer of stone from the Salt Lake City Temple, not just the capital’s most iconic structure, but that of an entire religion.

Curtis Marsh, Communications Manager for the firm, joked about the seriousness of such a task on such an important religious building, “They talk about seven years bad luck breaking something—try eternity.”

But Josh’s delicate touch on the machine performed the work without a blemish.

The company leads in this type of material preservation and reuse work. One famous project was demolishing Geneva Steel, the World War II-era steel foundry in Utah County.

“It took us three years to take it down,” said Josh of the gargantuan campus. “Everything was massive.”

How massive? 250,000 tons of steel dismantled. One piece of slag under a blast furnace was so large that it needed to be lanced by specialized machines to prepare it for transport to its final destination in China.

Other projects had similar sustainability triumphs. The team reported recycling 98% of the demolished material in the Salt Lake Airport by weight, well ahead of requirements from Salt Lake City to recycle 50% or more of demolished materials by weight. Team members see standards only becoming more stringent as the benefits of recycled material grow in importance, but executives are ready to go above and beyond those requirements.

Tearing Down to Build Up

The work of demolition is a lot more than “boom goes the dynamite” and watching a building collapse, even if that’s been a staple for the company’s 40-year history.

“We can make buildings blow out, come in, do all sorts of things,” said Josh. Gone are the days of ball and crane and pulley excavators; today’s machines are high-reach excavators with bucket and thumb attachments. The team described one of their machines as “the jaws of life, but for destruction.”

Watching time-lapse footage of the high-reach excavator taking down a downtown Salt Lake building is akin to watching scissors cut through paper.

Advances in demolition technology and machinery give demolition teams more control than ever before. A cage over the operator and a tiny camera on the end make sure cuts and demolition are not just performed at the highest level of precision, but done safely.

Safety is tantamount to this trade, with Josh and Nephi saying that team members are authorized to perform work stoppages and shut a job site down if they feel that safety is compromised.

Nephi and his step-brother and fellow owner Dylan Edwards were tasked to take the safety-first approach to demolition to the Lone Star State. Texas has been good to the company as it has enhanced its own salvaging and recycling capabilities. Nephi mentioned that, in Houston’s marshy terrain, aggregates are invaluable and have helped the company to continue improving in sustainability. Working with different oil and gas clients in Texas, he continued, has opened up work across the Gulf Coast.

The safety-first culture opened up opportunities outside the US, too. The company was contracted to travel to New Zealand and perform demolition work after the Canterbury and Christchurch earthquakes that occurred in 2010 and 2011. Grant Mackay Demolition was contracted to take down the tall buildings that were deemed unsafe for occupancy—one of five companies authorized by the local government to demolish buildings over five stories. They were the only American company to perform that work and the only company that did not have a collapse in two and half years working there.

The company’s 0.62 EMOD score is a testament to its safety culture, Nephi stated bluntly, “Safety is first and foremost. Above money, above our name—we have to create a safe environment.” He spoke of how the company has reported all near-miss incidents to find areas to improve safety, and all employees “Stop Work Authority” has made a positive difference, too.

“That [authority] goes to every level,” he said. “Even people who are just laboring on the ground for us. They might be able to see something that an operator can’t see.”

Exciting Times Ahead

For the entire Grant Mackay Demolition team, this legacy of safety, preservation, and sustainability that started 75 years ago still permeates their craft today.

The company demolished its own headquarters and performed the excavation work to prepare for its recently built office in West Bountiful. Their team tore down the old Sears department store downtown and is currently demolishing the rest of the remaining buildings at the Utah State Prison—a major project for 2023.

Reflecting on all of these historic projects both present and past brings some nostalgia-laden smiles, but no one is lost in a daydream. None have forgotten the work that has pushed the company to prominence, even as Josh called the efforts “a day at the beach.”

“The days that I hop in the excavator are the best days I have,” he said. It’s challenging work, but the effects are rewarding to the Grant Mackay Demolition team and the community, especially when seeing the work this company has performed across the state over the years. Demolition may be an often-overlooked part of the built environment, but its preparatory nature and power to change make it unforgettable.