Run Aground

How the global supply chain breakdown impacts Utah's economic shores. By Emma Penrod

For better or worse, economic trends in Utah have always lagged a few months or even years behind the U.S. as a whole. The supply chain disruptions triggered by Covid-19 and perpetuated by one global calamity after another have been no exception. Utah’s response to the virus may have been relatively lenient, but like the coming of the Transcontinental Railroad, we all watched and waited as the aftermath of the virus approached from both coasts.

The bulk of the supply chain disruptions finally arrived in Utah about halfway through last year, Josh Van Orden, President of VO Brothers Mechanical, recalled. Everything from natural materials to parts and equipment such as chillers, boilers, and pumps suddenly cost more, and shipping times multiplied—if those materials could be had at all.

“Items that have multiple components have enormous lead times, and sometimes come with an undefined delivery time,” Van Orden said. “We’ve had equipment come with a 24-week scheduled delivery. Stainless pipe vendors have indicated a 98% price increase mid-March due to nickel sourcing out of Russia stressing other suppliers.”

Even with a second wave of shortages on its way, Utah is likely positioned to fare better than other states when it comes to access to construction materials, according to Tim White, Director of Marketing for Utah-based wholesaler Mountainland Supply. But it won’t necessarily be immune, he said.

“There are logistical issues in terms of being landlocked—in one way that’s what has protected Utah for years and years and years,” White said. “But as we are entering into a global economy as a state, as Silicon Slopes is happening … getting product here that you need just takes a while.”

Waves at the Ports

Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC) estimates that total construction input costs rose 23.6% over the last year. But the rate of increase depends on the product. This past January—which saw overall prices increase about 3.5% compared to January 2021—softwood lumber, plumbing fixtures, concrete, and crude petroleum had the fastest-growing price increases, according to Chris DeHerrera, ABC Utah president and CEO, while metals including iron and steel finally experienced some price relief.

Metals including copper, aluminum, platinum, and especially palladium and nickel are expected to rise again on account of the Ukrainian-Russian conflict, DeHerrera said. About 10% of the world’s nickel, a key component of stainless steel, is produced in Russia, as is 40% of the world’s palladium, which is used to make catalytic converters and microchips.

A year before this latest crisis began, White said, the lack of available resin to make pipes and other products represented the major pain point. Severe storms in early 2021 hit the three largest resin plants in the U.S—all located in Texas—and for the better part of the year, it was difficult to even find available resin pipe, no matter the price.

The impact of these unrelated catastrophes may seem outsized, but it all began in 2020 with Covid-19’s global outbreak, according to Tom Berry, CEO of the Institute for Supply Management, a nonprofit dedicated to professional education.

While there was a span in late 2020 and early 2021 where manufacturing in nearly every economic sector ground to a halt, production has, for the most part, returned to pre-Covid levels, Berry said. The problem now is resolving the wave-like activity that has developed in global shipping chains.

Ports, like factories, shut down during the initial Covid-19 outbreak. Shipments already in transit couldn’t just freeze where they were, so products began to back up at the ports. When the ports opened again, they moved the backlogged products all at once.

The release of this backlog created that wave-like effect in global supply chains, Berry explains, because of the imbalanced distribution of manufacturing versus consumption around the globe—in general, wealthy countries consume more than they produce compared with other countries with lower labor costs that often produce more than they consume. As the first waves of ships arrived at, say, European ports, there wasn’t enough product to fill them up and send them back. This resulted in a shortage of shipping containers when the empty ships backed up at one set of ports and product once again backed up at the others. Similar dynamics have impacted overland shipping, whether by rail or truck.

The world has been trying to break the cycle ever since, but every time a crisis disrupts the production side of the equation, the cycle starts anew. Meanwhile, ongoing labor shortages and generally good business policies—it doesn’t make sense to build a bunch of expensive new ships in response to a temporary problem—have further entrenched the wave-like shipping trend.

Inland Insulation

Utah’s landlocked nature kept it relatively insulated when the first shipping waves hit the ports. But that isn’t the only reason why Utah was spared the initial impacts of global shortages—the state’s vibrant construction industry can also take some of the credit, White said.

When manufacturers realized they faced production and shipping backlogs that could take years to resolve, they started to prioritize, White said. As a business, if you have two orders and the ability to fill one of them, you’re going to go with the customer you believe has the greatest potential to place orders in the future. In the case of the last few years, suppliers have been betting on Utah, White said.

“That’s a roundabout way of saying our economy is so good that manufacturers have made allocations to us appropriate to the growth we are having,” White explained.

However, being landlocked isn’t always an asset—even with supply chains running smoothly, it takes longer to get materials to Utah than it does to coastal areas. As we know, the shipping waves eventually hit Utah, too.

Some products were spared the supply shocks entirely. Mountainland was able to continue providing certain bathtubs, for example, without significant delays because it just so happens that the company that makes them is located in Utah, White said. But manufacturing in Utah is generally limited. This means that even though Utah produces sizable quantities of natural materials such as copper and gas, the state was still subject to shortages of copper pipe and wire because it lacks the facilities to take these homegrown materials and turn them into products. As in many other cases, copper mined in Utah is shipped elsewhere for fabrication, which subjects it to the wave-like action of current shipping lines on the way out and on the way back.

“The more [manufacturing] capability we have, the less we will be impacted by these supply chain issues,” White said. And disruptions, he said, happen every year, if on a smaller scale than in the recent past. “If we’re going to continue to have these hurricanes and weather conditions that shut these places down, it might be a good idea to diversify where these things are located.”

Building Local Supplies

Utah, like most of the U.S., has lost much of its manufacturing since the 1970s, and the current trajectory doesn’t seem likely to make locating industrial operations here any easier, White said. Geography counts against the state twice—Utah’s location not only means lengthier supply lines for anything fabricated in the state, but the mountainous terrain means homes and businesses are squeezed together. And as the population grows and increases in wealth, the acceptability of industry has declined.

“Our cities are getting to the point where they don’t want a huge manufacturing plant in their backyard,” White said.

It’s unlikely that a state like Utah—or any state in today’s global economy—can stand up to all the manufacturing capacity required to support itself. What the state really needs to ensure more resilient supply chains in the future, White said, is innovation to find new solutions for modern problems, and for builders and contractors to get more involved in government processes to ensure the conversation about the state’s future growth includes support for the trades, manufacturing, and entrepreneurship.

“It’s just recognizing the fact that maybe what was good for us was like candy—cheap prices from China taste good for a while, until they start giving you diabetes,” White said. “It’s great and everybody is making money until they’re not. You have to look at the whole chain and say, ‘Maybe this doesn’t work anymore.’”

Because if the last four years have a lesson for the state, he said, it’s that growth must be balanced—you can’t concentrate all your growth and wealth on one side of the planet and expect all the supplies and labor to come from the other.

Electrical contracting is competitive as hell. With a plethora of mega projects upcoming, a bidding war for the best electricians and estimators, and even a race to secure the energy to power Utah buildings, the competition at every level seems to grow more intense with each passing year. How can electrical contractors respond to upcoming trends and win work in the Beehive State? It Starts with Labor Ken Hoffman, Preconstruction Manager at Ludvik Electric, said that the competition for labor has been particularly fierce since he and his team began working on the New SLC International Airport some years ago. Competing for great people has always been the case, but the influx of high-level projects over the last decade, he recalled, “pulled everyone up” with drastic increases in wages that helped electricians bring more money home and brought in a cadre of workers from out of state to push jobs past the finish line. There is additional work to be done to bring in the next generation of fieldworkers to help build the state’s future, specifically the financial incentive to enter into a demanding, sometimes dangerous field. Contracting tech company ServiceTitan reports that salaries for entry-level electricians have risen 9.14% since the beginning of 2023, but is it enough? No, and it is hampering project execution. At a recent Urban Land Institute (ULI) Trends Conference, Hunt Electric CEO and President Troy Gregory offered a sobering statistic: currently, for every electrician who enters the trade, three electricians depart. Nathan Goodrich, Division Manager of Helix Electric, said that the industry needs to find solutions fast, as competing for the same people in a wage-based arms race is unsustainable. “We have to promote the trades as people are coming through high school,” he said. Exposure through industry days and other presentations is one way while granting release time for high school student workers was another that Goodrich mentioned as two ways to bring in the next generation of electrical contractors. Gregory agreed, saying that Hunt Electric and other industry groups have become much more involved at the high school level by showcasing and giving interested students career opportunities. He and his team have had success working on pre-apprenticeship that gives the most eager hands-on experience in prefabrication, an area that only grows in importance for contractors. “We’re getting them in a better position to be more productive on a job site on day one,” said Gregory.

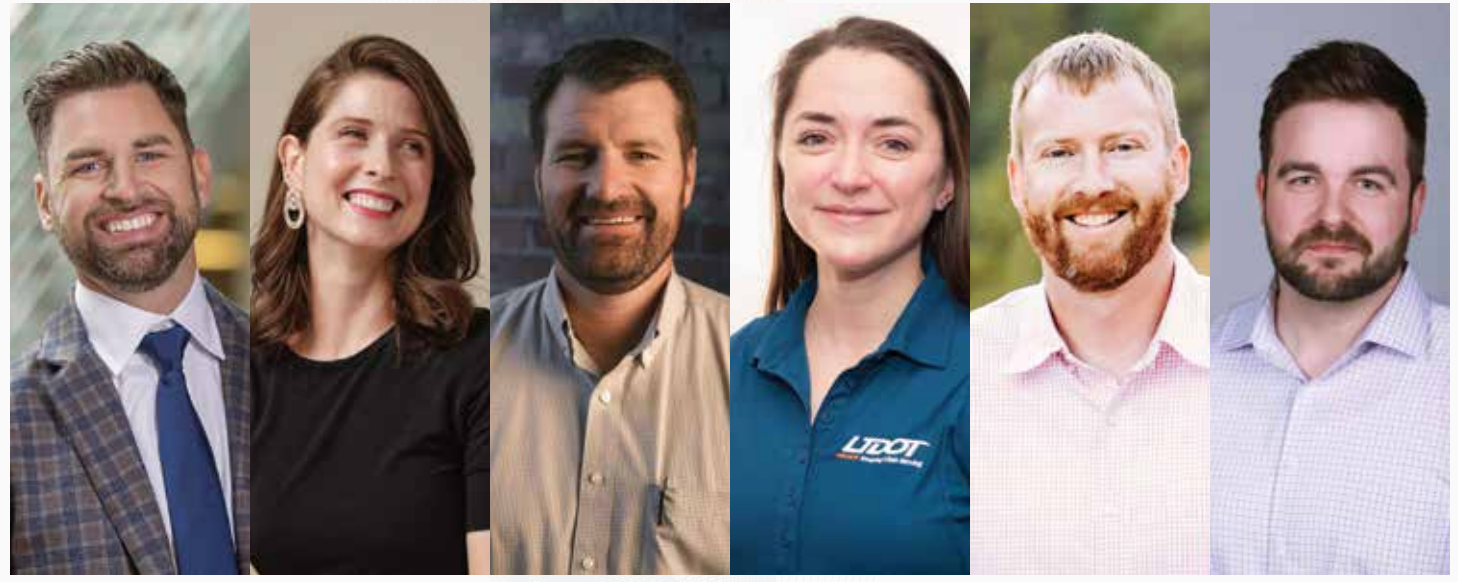

Editor's note: UC+D's annual look at age 40 & Under A/E/C professionals includes individuals from a wide range of market segments including a general contractor VP, an interior designer, a rising UDOT director, a steel industry entrepreneur, an equipment dealer owner, and an electrical contractor safety/HR executive. Each holds a key position at their respective firm and has proven their skill and capability along their unique career paths.

Architect Brian Backe was succinct when he stated, "when I try to describe the Climate Innovation Center, one of the phrases is 'big things comes in small packages'." His words couldn't be more profound. An ambitious adaptive reuse project that is generating significant buzz in the sustainable building arena locally, Utah Clean Energy's new Climate Innovation Center (CIC) is the transformation of a modest, nearly 70-year-old, 3,000 SF single-level commercial structure into a state-of-the-art, two-story, zero-energy building that will serve as UCE's home for the next half century. "Within a 3,000 square foot footprint it has urban infill, is an adaptive reuse site, Net-Zero, combustion-free, hybrid mass timber structure—we really packed in a lot," said Backe, Principal-in-Charge for Blalock & Partners, who worked closely with Salt Lake-based Okland Construction to ensure optimum sustainability throughout the construction process. The $5.4 million, 5,260 SF project officially opened in June to much pomp and circumstance, and rightfully so. The center showcases the potential of what homes and buildings can be—spaces that are not only comfortable and inviting, but also produce zero pollution. The building will offer a space dedicated to learning, exploration and collaboration centered on climate solutions and improving local air quality, and a place for the community to engage and create solutions to the challenges we face. The project is a testament to CEO/Founder Sarah Wright and her team at Utah Clean Energy, and their commitment to increasing awareness of environmental sustainability. Their new home makes a bold, walk-the-walk statement about the importance of renewable energy in the built world. "There needs to be an education and understanding that renewables (solar, wind, hydro, geo-thermal) are our cheapest resources," said Wright, a Chicago-native whose diverse background includes work in geology, environmental consulting, air quality, and occupational health. She founded UCE, a mission-driven non-profit, in 2001 and is thrilled to see the CIC finally come to fruition after years of planning. The project, she said, embodies UCE's dedication to transforming Utah's built environment to be zero energy and emission-free, while helping the community reimagine the places we live and work. "This is a living laboratory and teaching tool for the public and the business community, demonstrating the tremendous role that buildings have in solving climate change," said Wright. "Everyone that's been here loves it and other owners say they are inspired by it." Kevin Emerson, Director of Building Decarbonization and an 18-year UCE veteran, said the project became a necessity in recent years as UCE's staff swelled to 15 people. "We've had a dream to really 'walk to talk' through our office headquarters and (CIC) is the result of that dream coming to fruition," said Emerson. "It is more than just office space—it's meant to be a showcase and teaching tool for the construction and design industry." "There is nothing more sustainable than reusing our existing buildings and breathing a new 50-year-life into a structure than was slated for demolition," said Backe, adding that construction crews seismically braced the primary existing CMU block wall, in addition to reusing over 65 tons of CMU and 50 tons of concrete.

Cancer sucks. That message is on t-shirts and stickers, message boards and social media, and is often said to others when news comes out about a diagnosis—a show of solidarity in the fight against cancer. But riding through the challenge doesn’t have to be the only experience, especially in cancer center design and construction. For Nathan Murray and Brian Murphy, the respective design and construction leaders who helped bring the McKay-Dee Cancer Center into a 21st century, their work showed that a cancer diagnosis or treatment isn’t the end, but the beginning of a new journey of support and patient-centered care. The project was a long time coming. What began in 2018 with the winning bid needed a bit of time to settle on the ownership side, but had Scott Roberson and Jimmy Nielson from Intermountain Healthcare championing the project along the way. Throughout the project, the team never lost track of the patient experience, which Murphy said led to many productive meetings on design priorities and project sequencing to achieve the renovation’s full potential.

As the commercial construction market in Southern Utah—particularly Washington County—continues to heat up, Onset Financial's dazzling new four-story corporate headquarters for its Red Rock Division makes a bullish statement about the company's outlook for the greater St. George area. Indeed, the owner-occupied structure totals 60,000 SF and is designed to harmonize aesthetic appeal with supreme functionality, given that it houses 23 offices, 86 cubicles, myriad state-of-the-art amenities, and a swanky top-floor corporate penthouse for Onset owner Justin Nielsen that is second-to-none. Developed by Salt Lake-based Asilia Investments, CEO Jonathan (Jono) Gardner stated frankly that this project is the nicest, most expensive office project per square foot that his firm has been involved with, and it speaks to Onset's aggressive business practice and optimism in the future of the equipment lending market. "You walk into that building and you know you're in something special," said Gardner. "It's [Onset Founder Justin Nielsen's] way to attract talent. He said, 'This is the way I'm going to build my business,' and he put his money where his mouth is, [wanting] to go above and beyond anything in the market. He leaned into this with an attitude of 'this is my business, this is my operation, I want people to know this is the place to be.’ He has incredible vision and can see things before they happen." Designed by Salt Lake-based Axis Architects and built by Salt Lake-based Okland Construction, the two firms worked harmoniously with each other via a CM/GC delivery method to produce one of the most unique structures imaginable, with a highly-complex layout where two gridlines intersect each other at a specific point in the middle of the building, with the layout based off this one intersection in all directions and floors not situated directly above each other. Gardner charged the design team, led by Pierre Langue, Founder of Axis Architects, to "give us something we've never seen before." In addition to the unique floor layout from floor to floor, they wanted to take advantage of incredible views into Snow Canyon and the environment in general, along with being situated along the Santa Clara River, which offers its own unique aesthetic beauty. Langue pointed out his firm’s perpetual refinement of using "apertures"—a "design element we've been developing and including in our designs for 20 years that is a continuation of an effort instead of one individual design," he said. "It's in reference to a camera—you're inside a box and framing the view. It's a great feature on the inside because you can frame the different views." “That's why the [floor] plates are rotated. It gave us a way to focus the view on something very specific that you want the viewer to see." In addition, said Langue, apertures on the outside are used as an extension of the building and help create shading for the large expanses of glass. Designing the complex floorplate grid was one thing, building it was another. "The layout was difficult because the gridlines were not particular to each other, and they didn't necessarily transfer to the floor above," said Tyler Dehaan, Project Manager for Okland, adding that it's the firm's first project of this kind. He said the "first pier footing we poured was crucial"—it had a column that extended at an angle and only connected to the building at the top floor, and was 15 feet lower in elevation than the first floor. "I was really concerned about that column not being in the right location/elevation and then the steel column not fitting," he added. Dehaan said they wouldn't know for six months if everything would fit—until all the footings, the foundation, three concrete cores (two stair towers, one elevator), and structural steel up to level four were completed. "In the end, it fit perfectly," said Dehaan. "There were no issues." Pouring the three cores was both challenging and labor intensive, and because structural steel tied into the cores, construction on steelwork had to wait until they were built. Okland self-performed the slip-forming process with help from some experienced concrete subcontractors. "When you see what's going on with the structure, you see the genius behind it," said Gardner. "The common cores hold it in place." Another critical and highly unique construction aspect was building a robust “sea wall” along the Santa Clara River capable of withstanding a 150-year flood event. Nielsen had concerns about the building being so close to the river but also wanted a dynamic outdoor terrace with direct access to a bicycle/running path along it. Hydraulic consultants collaborated on a “belt and suspenders” type of decision, said Dehaan, with crews digging down 15 feet below the main floor and installing a retaining wall below the flow line of the river. A wall of riprap and large cobble rocks were installed after the retaining wall was completed and during backfill. A similar build was done along the dry wash on the other side of the site.

Out with the old, in with the new? Not quite, according to experts in the mechanical industry. Trends in mechanical engineering and contracting are warming to both new and existing solutions to optimize efficiency as they maximize the mechanical budget. Three mechanical professionals in design and construction detailed the trends they see helping current clients integrate these mechanical solutions with the future in mind. Electrification Buzzing; Heat Recovery Heats Up According to Jared Smith, PE and Mechanical Engineer at VBFA, a constant in the mechanical field is that many owners have continued with gas-powered systems instead of fully embracing electrification. “The high first costs of full electrification of the mechanical systems through heat pumps,” Smith said, “is a bridge too far for owners currently.” “We’re not anywhere near full electrification of every project,” he said, “but clients are toying with the idea, and more clients are getting serious about it.” Operational costs are favorable due to the heat recovery nature of the system, but Utah’s location in a heating-dominant zone (colder winters) means that more air-source heat pumps would be required to meet the building’s heating needs than necessary during the summer months. Widespread electrification may be a years away, but it is is trending up, making the relationship between mechanical and electrical teams more important than ever and setting the stage for future project team victories in coordination and collaboration. It will become the standard for younger engineers as the industry heads toward full electrification of building systems, Smith said. It’s just one of the upcoming trends he is most excited about in the world of mechanical systems. Another is the efficiency gained through heat recovery chillers. Like a heat pump, heat recovery chillers pull heat out from a cooling source. During the cooling operation, the chiller produces cold water while dissipating heat through the condenser. But with a need for both chilled water and hot water, the released heat can go toward heating application. Smith said that operations are seeing overall energy usage intensity decrease across the square footage of the building. Wasatch Canyons Behavioral Health and Intermountain Health’s Saratoga Springs Cancer Care Clinic are two examples where Smith and the VBFA team have seen energy usage intensity decrease with the future implementation of a heat recovery chiller. “It shines in the healthcare environment,” Smith said, “with the year-round cooling load, you can dump it back into the heating system.” Electrification Still Needs Work; “Thermal Battery” Shows Promise For Steve Connor, PE and President of Colvin Engineering Associates, the University of Utah is fast becoming a leader in the electrification of new buildings. “By heating buildings with electricity, what was once heresy,” he laughed, “has become gospel.” Connor cautioned that electrification has drawbacks that need to be considered, namely that building electrification could create a second peak use period in the winter, one which could be even higher than current summer peaks. It will be incumbent on the A/E/C industry to continue to make gains on what Connor called “the best investment in energy” via high-value insulation, building envelopes, and windows to minimize the need for heating. The next step is to recover and store energy generated. At the new James LeVoy Sorenson Center for Medical Innovation at the University of Utah, Colvin Engineering Associates, along with trade partners Archer Mechanical, are utilizing a 42,000-gallon water tank that will function like a thermal battery for the building when it opens in spring 2026. Heat pumps will use the tank as a heat reservoir, adding or withdrawing heat as they cool or heat the building. If the heating demand is especially high and the tank gets cold, they will “charge” the tank overnight with an electric boiler, and if the tank gets too hot in the summer, they will reject the excess heat through a cooling tower. Most of the year, they add or remove heat from the building and store the waste heat in the tank, making it function like a thermal battery. Since buildings are always in need of cooling due to the energy use, people, and equipment in use across the building, heat can be taken away and stored in the tank before being pulled out of tank to heat the building back up in the morning.

The business didn’t technically start, as Matt Menlove put it, with five guys in their father's truck. But it was the impetus for Matt and brother Marc to start United Contractors and take it to the heights reached over the last 20 years. One thing that came from those times working out of Dean Menlove's truck was this: “We were taught a love to build,” said Matt, who now leads the 56-person business as CEO. Their upbringing put them on the path to start United Contractors, but not before a few other iterations. The brothers’ handyman business, Menlove Maintenance, helped put the two through college. MKM Construction, run by Matt, ran for a few years before he and Marc joined forces to start United Contractors. United Hits Stride with a Company Vision The early business had the same, “out of your truck” mentality, with United’s first job renovating a Marriott hotel lobby near the Salt Lake City airport, and another significant project by the airport—renovating a tilt-up building for pipeline supplier T.D. Williamson. The 60,000 SF renovation included building a new mezzanine and outfitting the building for industrial operations on a small budget. The project was so successful that the client asked if we could stay on call for future building needs. “That was our first repeat client,” said Matt. “That was where we began the vision that ‘Every client would choose us again.’” At a recent company party to celebrate their milestone, Matt joked that the name "United Contractors” made it sound like they were a bigger business than they were, a benefit of the doubt that may have allowed the company a foot in the door initially. But company size and capability have never mattered as it relates to the company vision—that good experiences on the project team would bring in more work. “Our mission has always been to consistently exceed expectations through ‘Building on a Promise,’” Matt said. “As we build relationships and our clients trust us, then we can get to know them and begin to supersede their expectations and win them over again and again.” It’s not just clients that United wants to win over with the team’s attitude, work ethic, and understanding of construction, he continued, “We want to win over design partners, subcontractors, vendors, and even employees [...] It’s what we strive to accomplish every day when we step on the job site. “

It's been a decade since Kimley-Horn, one of the nation’s top engineering and design consultancy firms, launched an office in Salt Lake, and by all accounts, the Wasatch Front market has been a boon to the civil engineering firm, with local leaders feeling highly optimistic about its future success and growth in the Beehive State. The Salt Lake office was opened by Zach Johnson in 2014, who previously spent time in three other Kimley-Horn offices including Sacramento, Orange County, and Denver, with three total people comprising the initial staff. The firm's Denver office was providing consulting services for the Utah Department of Transportation and put together a market analysis regarding expanding into its neighbor to the west. "The market analysis we put together showed we should have had an office in Utah 10 years previously [2004], so we decided to plant a flag and open an office," said Johnson, who leads the office along with seasoned Salt Lake office practice leaders Chris Bick, Leslie Morton, and Nicole Williams. Like any new start-up endeavor, it was rough sledding initially, but strong regional support and the sheer tenacity of boots-on-the-ground marketing started paying off, with explosive growth happening along the way. "I would describe the first few years as lean," said Johnson. "We had to be creative, we had to be scrappy to capture work and rely on our partners across the country, folks who had clients in Utah and rely on those relationships. Those first two to three years were about relationship building and knocking on doors that didn't always open. It was a lot of fun."

Nearly 90 minutes into a conversation with Dave Edwards and Bruce Fallon, the two remembered a story about the values of WPA Architecture from years before. Fallon was in talks with the principals at the firm to define values for the rest of the company. Longtime ownership, with decades of experience founding and building up their own firm, weren’t against the idea, but the idea of formalizing it all seemed inconsequential. Fallon had been a Principal with the firm for ten years and finally asked longtime Principal Alan Poulson (who retired in December 2023), ‘What motivates you?’ to which [Poulson] answered, ‘Providing for my family.’ The thought has stuck with Fallon and Edwards ever since. “It drove [Poulson] in everything he did,” Fallon said. “He was excellent in everything he did so he could provide for his family.” Now that the two lead WPA as Principals, they have looked to embrace excellence through intentionality—in purpose, relationships, and work ethic—that will lead the firm to new heights.